Paper leaves its (water) mark

Writing manuals – primarily Renaissance and Baroque (now referred to as early-modern) period books – were foremost in my mind in 2015. What I wasn't much interested in was American 18th and 19th century penmanship books. There are a multitude of penmanship books published in this period. Why cover ground so thoroughly described by Ray Nash?

At the outset of my trip in 2015, I had hoped that I could enlist librarians to work with me in making a database of early modern writing manuals in US collections. I couldn't do it alone, and a ride around the country talking with librarians might build into a crowd-sourced effort. As an independent scholar, I was without institutional resources, and didn't have the financial means to conduct a survey on my own. Grassroots scholarship by motorcycle was the method I chose to build support. It's good to have a goal, even if it changes along the way.

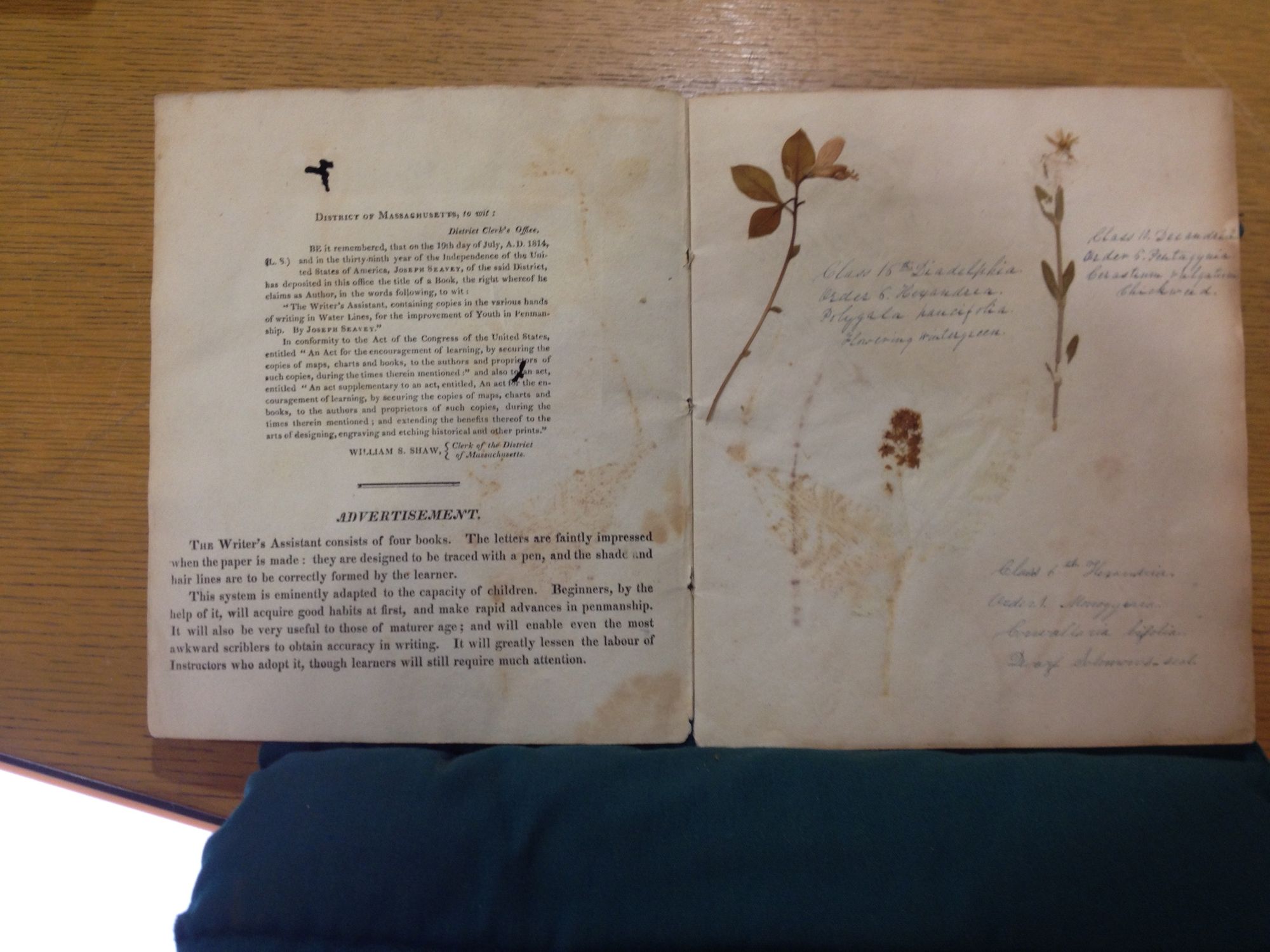

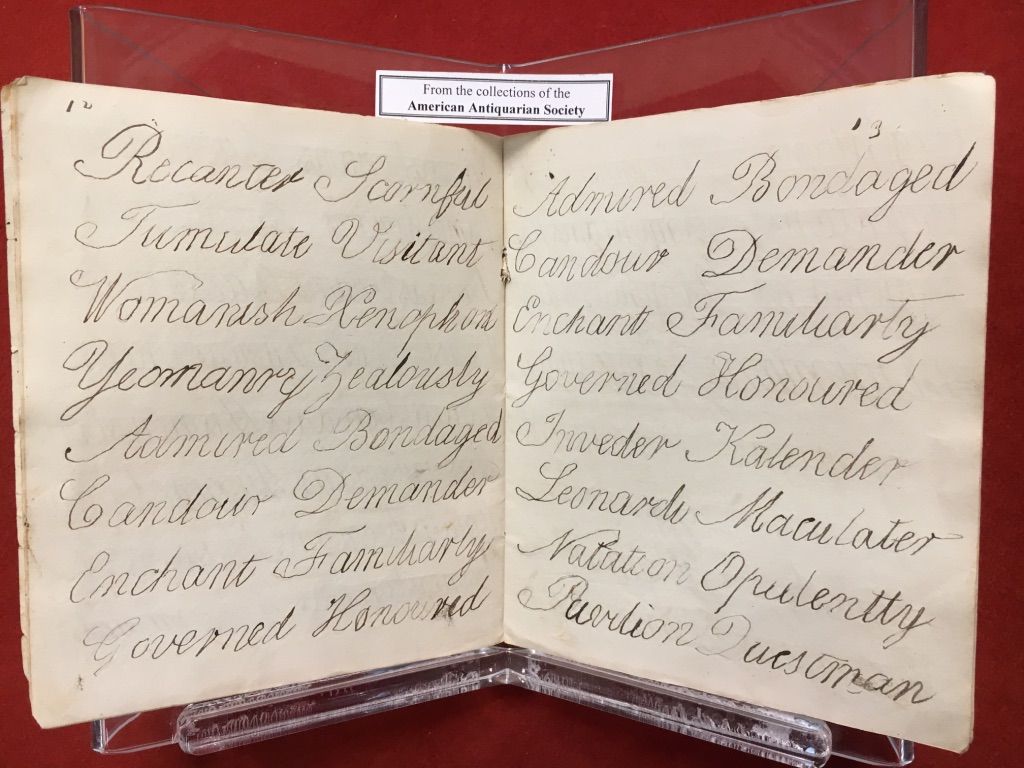

When I was at the Newberry Library, Paul Gehl and Bob Williams wanted to show me a gift from David Becker, a print scholar and author of The Practice of Letters: The Hofer Collection of Writing Manuals, 1514-1800. David spent months at the Newberry Library comparing writing book titles held by both institutions, so in thanks he gave them The Writer's Assistant: containing copies in water lines, for the improvement of youth in penmanship by Joseph Seavy. Bob and Paul wanted me to see this book because it was so unlike other writing manuals or copybooks. All the illustrations for practice were made as watermarks. This meant that, at a minimum, 1,000 letterforms were made in wire and sewn to the cover (wire screen for wove paper) of the mould! Paul thought it was an interesting anomaly, and a thoughtful gift to the Newbs from our mutual friend, David Becker.

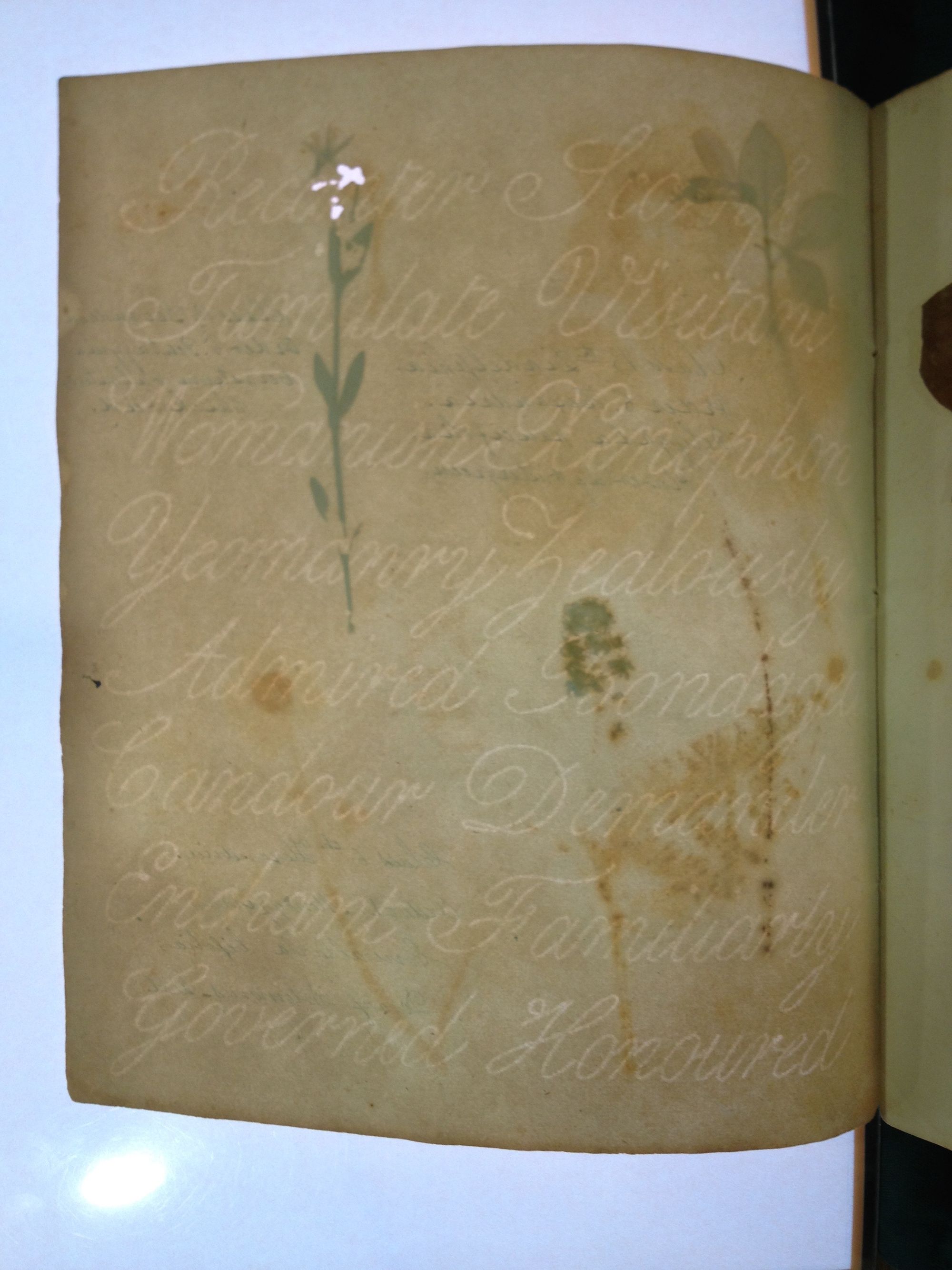

When I first saw it, I was confused. This was some 19th century writing manual with a long-assed title that had a bunch of plants woven into it to make an herbarium.

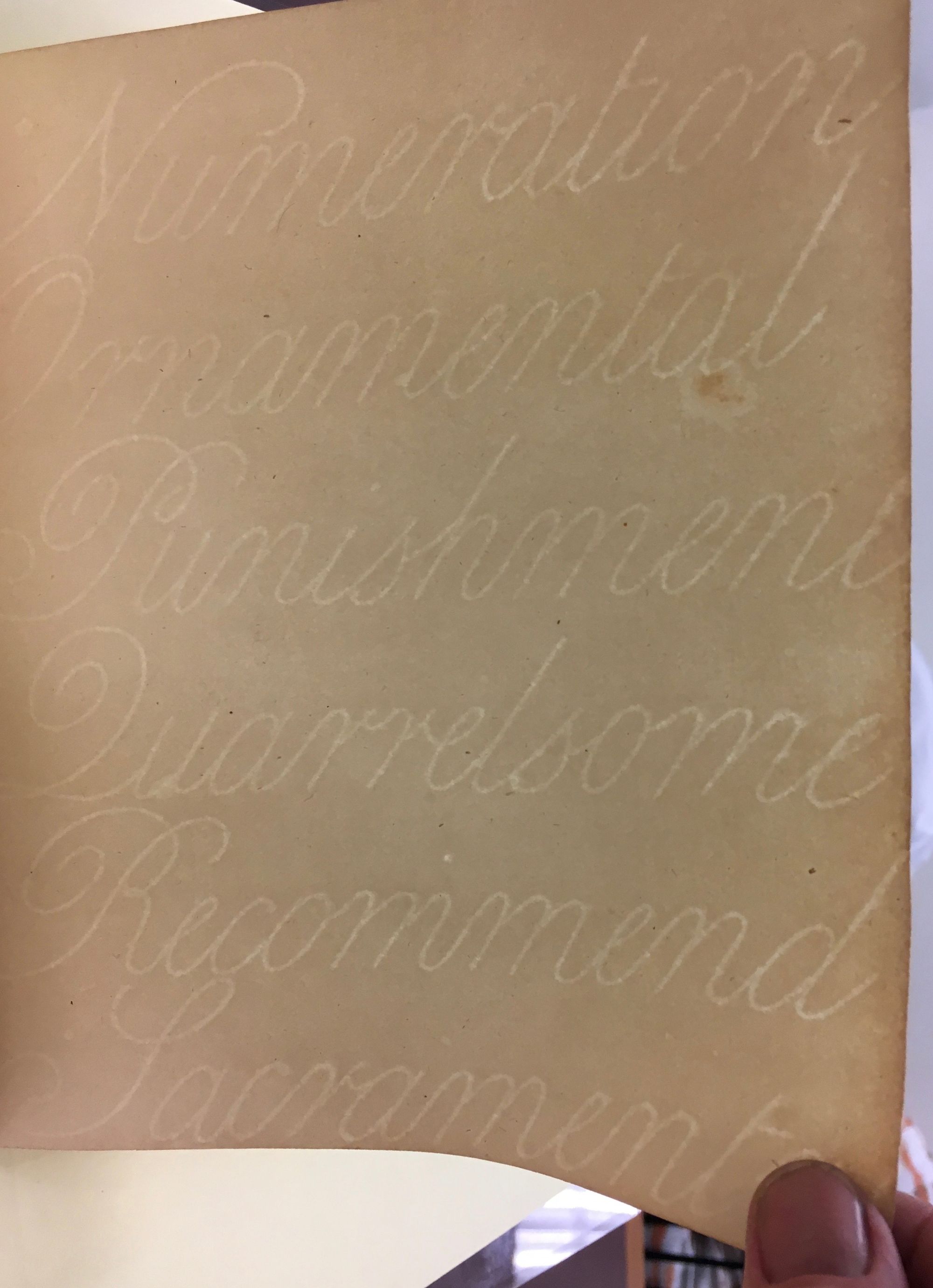

But, there, faintly in the paper were letterforms, subtly ranging down the page, just like a printed copybook. Looking at the sheet with the plants, some late 19th century notes, I was attempting to decipher what I was looking at. But then, I was instructed to begin to turn the page - only to discover that those letters were watermarks, quite clearly a part of the papermaking.

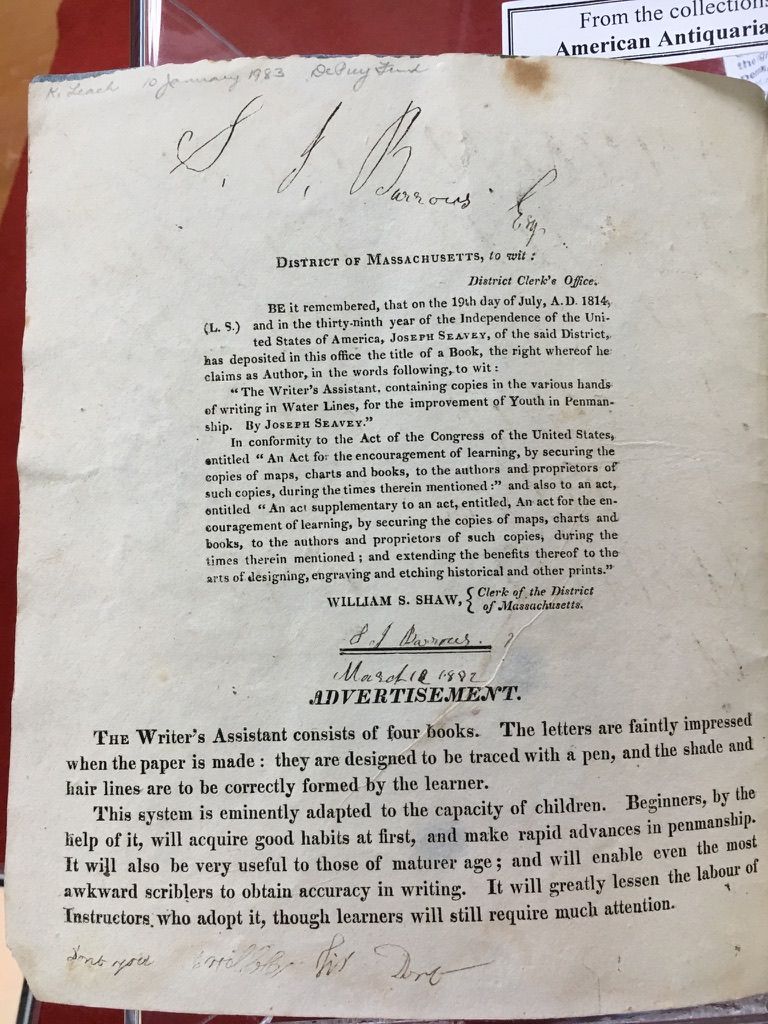

The title of the book uses the term "water lines." In the advertisement at the bottom of the front cover, it states: "The letters are faintly impressed when the paper is made: they are designed to be traced with a pen, and the shade and hair lines are to be correctly formed by the learner." I was puzzled by this phrasing, and excited by the approach offered. "The letters are faintly impressed when the paper is made..." My understanding of a watermark is not that the wire-form that creates it is impressed on wet pulp. Rather, the pulp slides off the highest points on the mould cover, resulting in less pulp at that point. This allows light to pass through that thinner part of the sheet more easily. I was confused by this description, as if the sheet were already formed, and a stencil of the letters was pressed into it. However, this made no sense because it would be adding a new step to the process.

It piqued my interest because it was a singular illustration method that provided for a direct practice method for copying. No intervening paper, no having to look at the copy, and try to remember what one saw when doing the work. The student wrote directly on the "illustration" and could then compare how well they'd done. I The simplicity of the process was far superior to the usual woodblock or engraved plate illustrations. It seemed that this was a unique method of teaching.

While not well versed in papermaking history, I had never heard of watermarks being anything but brand identifiers. Something like this would have been written about: Dard Hunter wouldn't have let something this amazing pass without notice, right? At the time, I was just too excited by the mystery of how this could have been done economically because at the first, I thought there were over 7,000 watermarked letterforms. I knew that a skilled craftsperson could accomplish the task, but at what cost? It appeared to be an expensive undertaking that defied publishing risks in the early 19th century.

When I searched WorldCat, I found that the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, MA held 2 volumes, as did the Massachusettes Historical Society. For a book that was offered for sale in dozens, or gross lots, that wasn't very many survivors. There was no mention in Ray Nash's work, and that excited me as well. I had already planned on visiting Worcester before being introduced to Seavy's mysterious title, but now I had a focus for my visit. I wanted to see if I could unearth any other copies of the booklets, and answer questions about its manufacture, whether it was well recieved (by the few institutions collecting it, I wondered if it sold very many copies), and how it was used. I couldn't figure out how the faint letters could show up well enough to copy without back lighting. It had to be able to be used by young students; I suspected a simple solution, but at the time couldn't figure out what that might be.

I've jumped ahead with this image of the page being used. I traveled from Chicago to Washington, DC, and up through NYC before reaching the American Antiquarian Society. It was a month of confusion, discovery, frustration, and meeting new allies before I had a few questions answered, and more created. While I cover a lot of this in my chapter in Papermaker's Tears, Volume 2, I'll go into more detail here in future posts.

Without knowing it, my original objective: A census of writing manuals in American institutions, had been shattered by this strange lacunae of publishing illustrations for training penmanship.