Knowledge Rises to the Surface

"Everybody knows what a good sheet of paper is," says Don Farnsworth as he recounts the story his half-century of papermaking. For most of that time, he's been observing and questioning: What made the Renaissance drawings different from what contemporary drawing on paper made today? As he says in A Quest for the Golden Fleece, "Rarely have I encountered an entangled mat of cellulose fibers I didn’t appreciate in one way or another."

Should you wish to follow along, I suggest reading his books: Handmade Paper: Method Cinquecento Renaissance Paper Textures; A Quest for the Golden Fleece; Mark Making – Line Quality: On paper made in the cinquecento method. Each one is available for free download on his site. Don updates these books as more is revealed to him through continuous research in the papermaking studio, through drawings, and observing historic papers.

"But, I ask: what makes a sheet of paper 'good'?" Don's probing question leads to a recounting of how he came to begin to understand the importance of surface texture in taking a mark. Because "...the underlying paper texture that defines the stroke is never the same," Farnsworth's curiosity has led to a concerted effort to analyze the manufacture of old paper, and emulate it. Based on observations acquired from making and using his paper, looking at historic paper used for drawing, book printing, intaglio printing, and other uses, Farnsworth teaches how to look.

As Don recounted his story, I picked away at sheets being made for a print edition that master printer, Tallulah Terryll is producing on the acrylic flatbed printer. With a medium stiff dish-scrubbing brush, a pair of very pointed tweezers, and my fingers, I stood for about 5 hours dehairing these sheets. For two days, while Don and Max Thill made paper, I dehaired sheets to make them ready for sizing.

Spending time proofing paper, observing each sheet as a suitable surface for printing can increase one's sensitivity to the factors involved in its manufacture. While a hairy sheet might be acceptable for one or more uses: drawing, or letterpress printing, it might not work well in another application. This kind of scrutiny increases my sensitivity while reducing the tendency towards black and white judgement.

Joking about what contributes to conditions where a sheet of paper is deemed good - belies the rigorous curiosity that Don has towards all aspects of paper and papermaking.

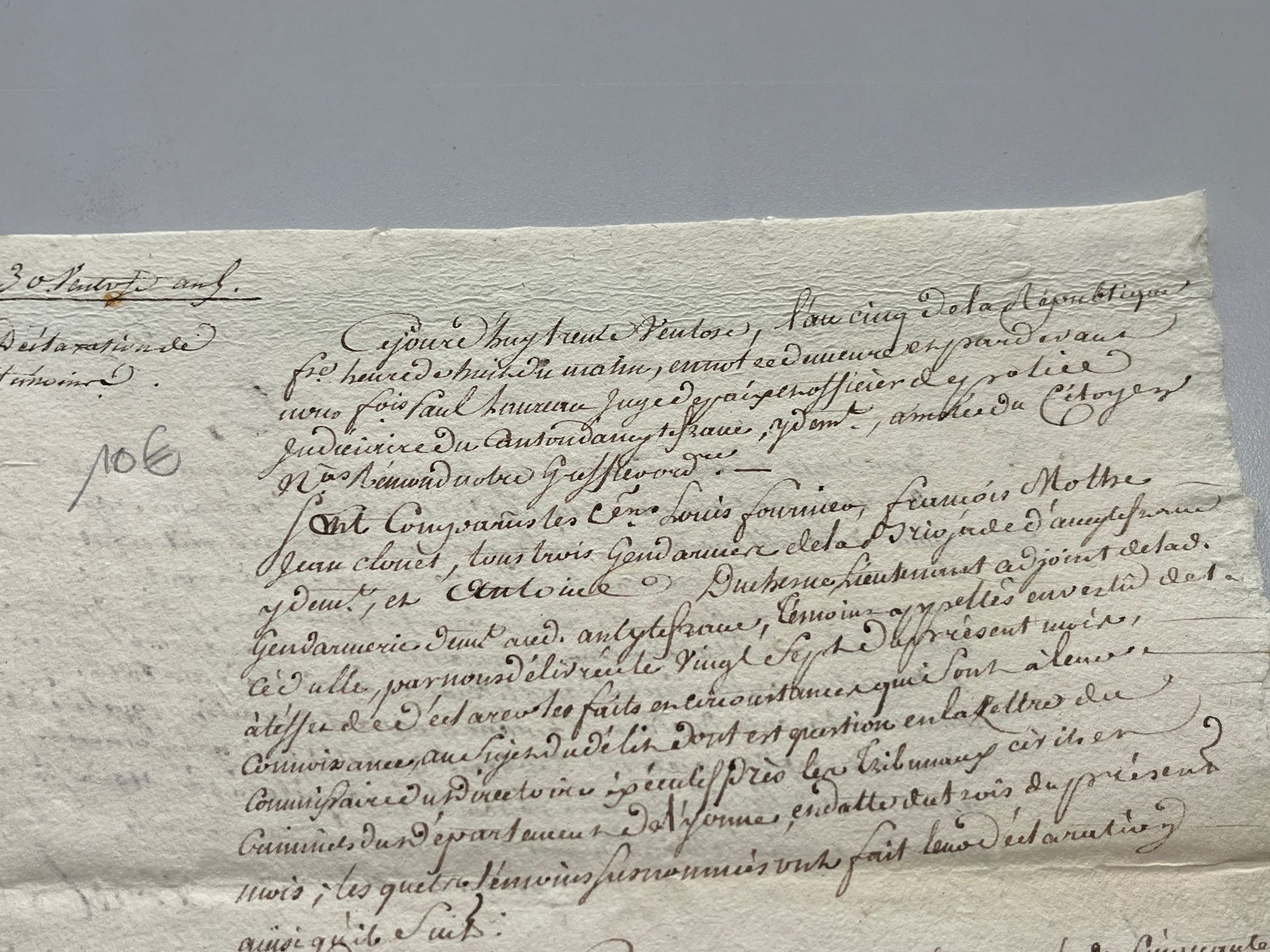

There are marks or textures that are in no way a mistake, or a flaw. Above you see a letter that is written on a loft-dried sheet of paper which was dried in a spur (4 or more newly formed sheets laid over a rope or pole). Identifying these and working out how they were produced is well documented in Don's books giving the resulting conversation greater weight because we were talking about the specific actions of a papermaking student and whether those actions were a mistake. They might be construed as such by the paper mill, yet they might be incorporated by an artist, printer, or correspondent.

My education as a papermaker is unfettered by academic concerns; I'm not in a graduate school program for book arts. My past experiences with books as a scribe, bookbinder, historian of the book, librarian, and business owner allow me the freedom to learn this new craft with the advantage of long experience with books. An Analysis and Review of Parchment-making Literature and Recipes was my bachelor thesis where I taught myself how to make parchment from historic descriptions and recipes. Each action and material leaves its mark. And each skin is unique, all of which can inform a researcher how those materials impact a manuscript book. While I never finished the research that I began then, I have spent much of my working life interested in how pre-industrial manufacturing processes hold information unseen by our uniform production-blinded eyes.

Volunteering at Magnolia Editions in the paper studio has rekindled my interests in what is now referred to as materiality of the text. What was once a fringe activity now appears to be mainstream research in the new world of digital humanities. In addition to learning a new craft, I'm refining my awareness of hand papermaking (even the industrial kind using Hollander beaters!) materials and techniques. Whether I make paper to write, draw, or print on, or I use this new-found sight as a researcher, my curiosity has been improved by this association.

In addition to the educational component, hanging out with a group of people who are solving problems, being curious, and making things is a welcome addition to my routine, much of which is spent alone, with my chickens.