Mercator's projection and tutelage

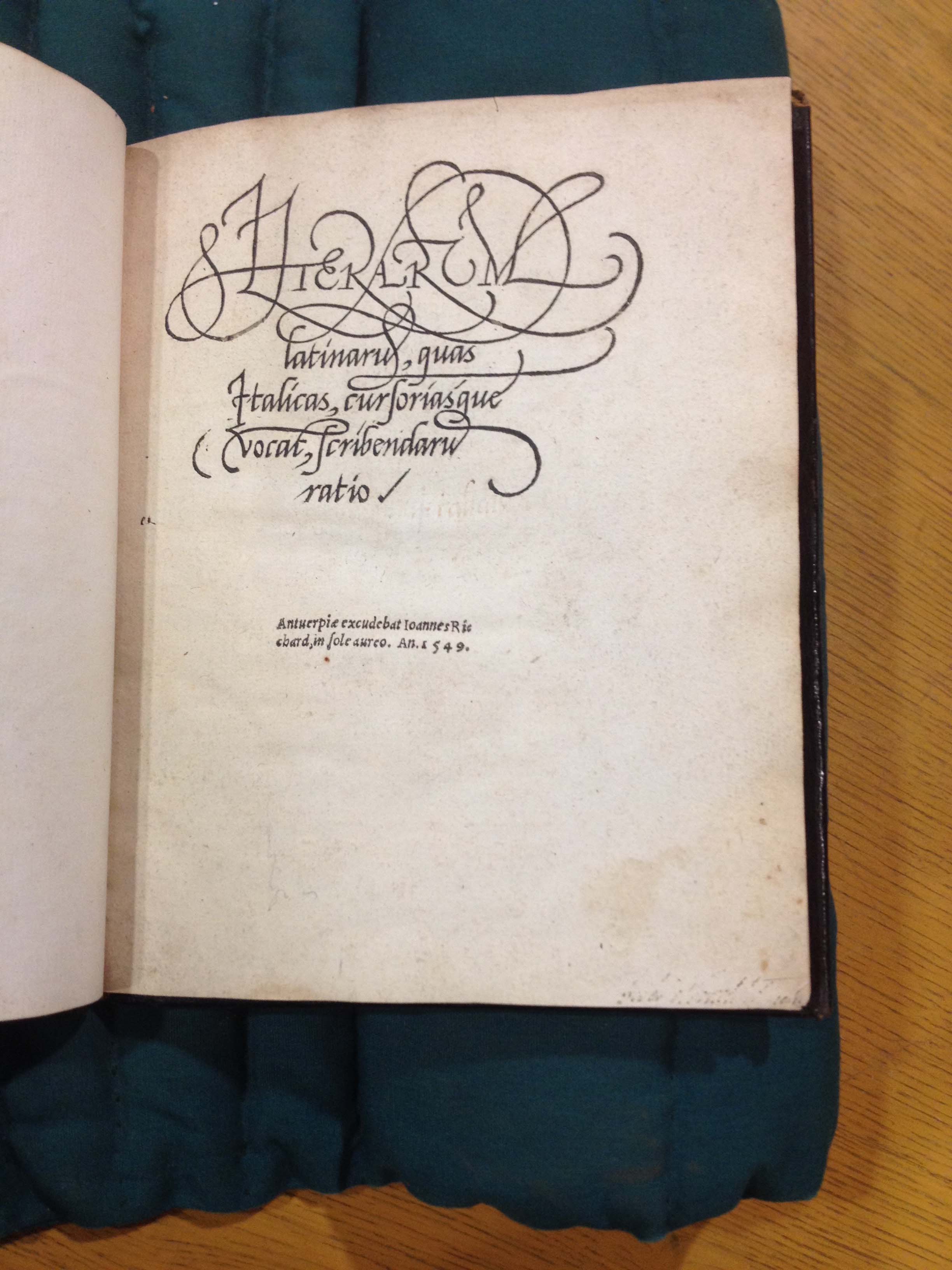

Italian 16th century writing manuals are numerous, however the rest of the Continent took about half a century to catch up with the innovators. Neudorffer in Germany, Iciar in Spain published prior to the middle of the century, but there was one guy over in Flanders that stood out. When Palatino was making a splash with his Libro nuovo d’imparare a scrivere Gerhard Mercator produced Literarum latinarũ, quas italicas, cursorias- que vocãt, scribendarũ ratio.

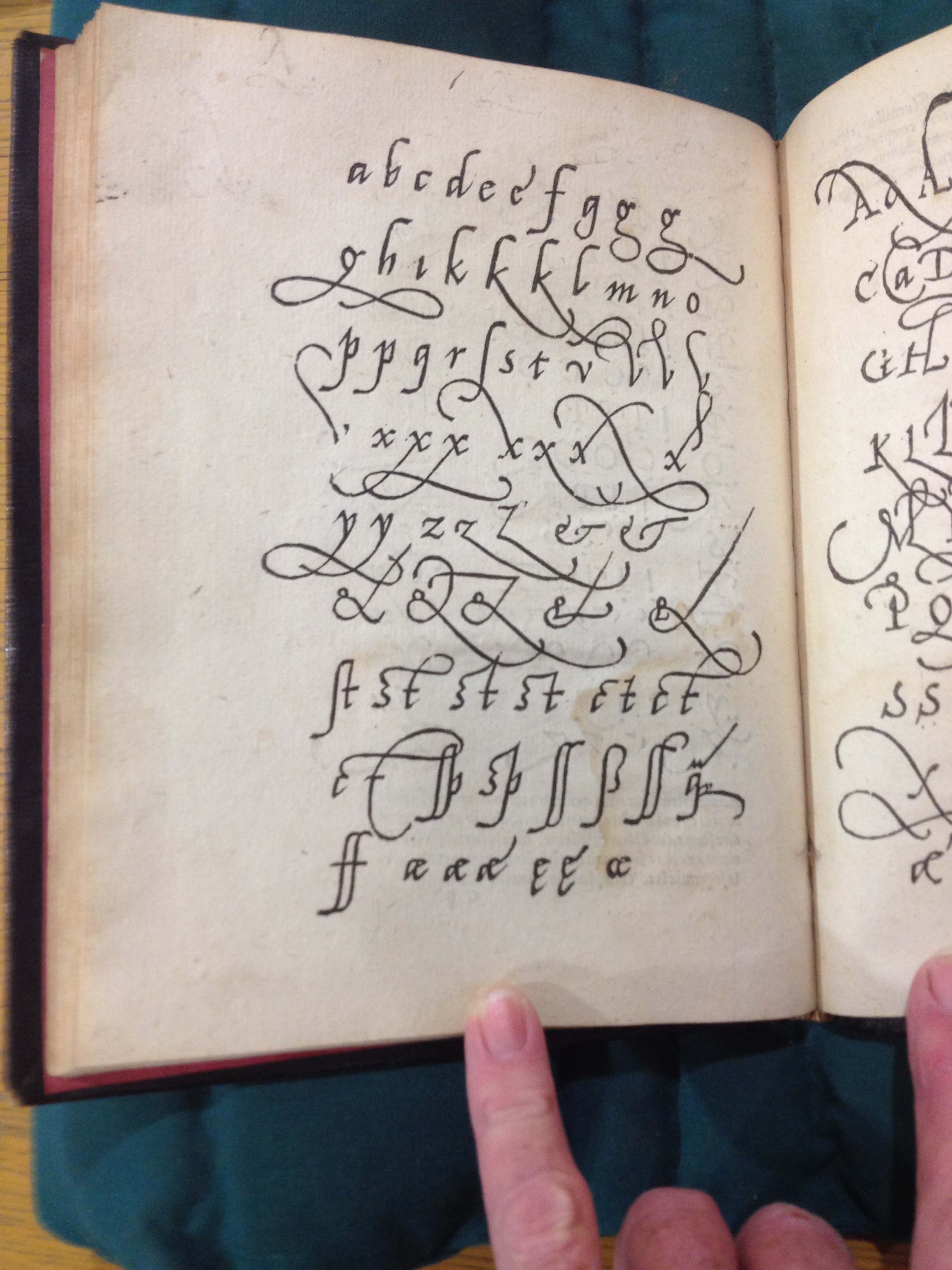

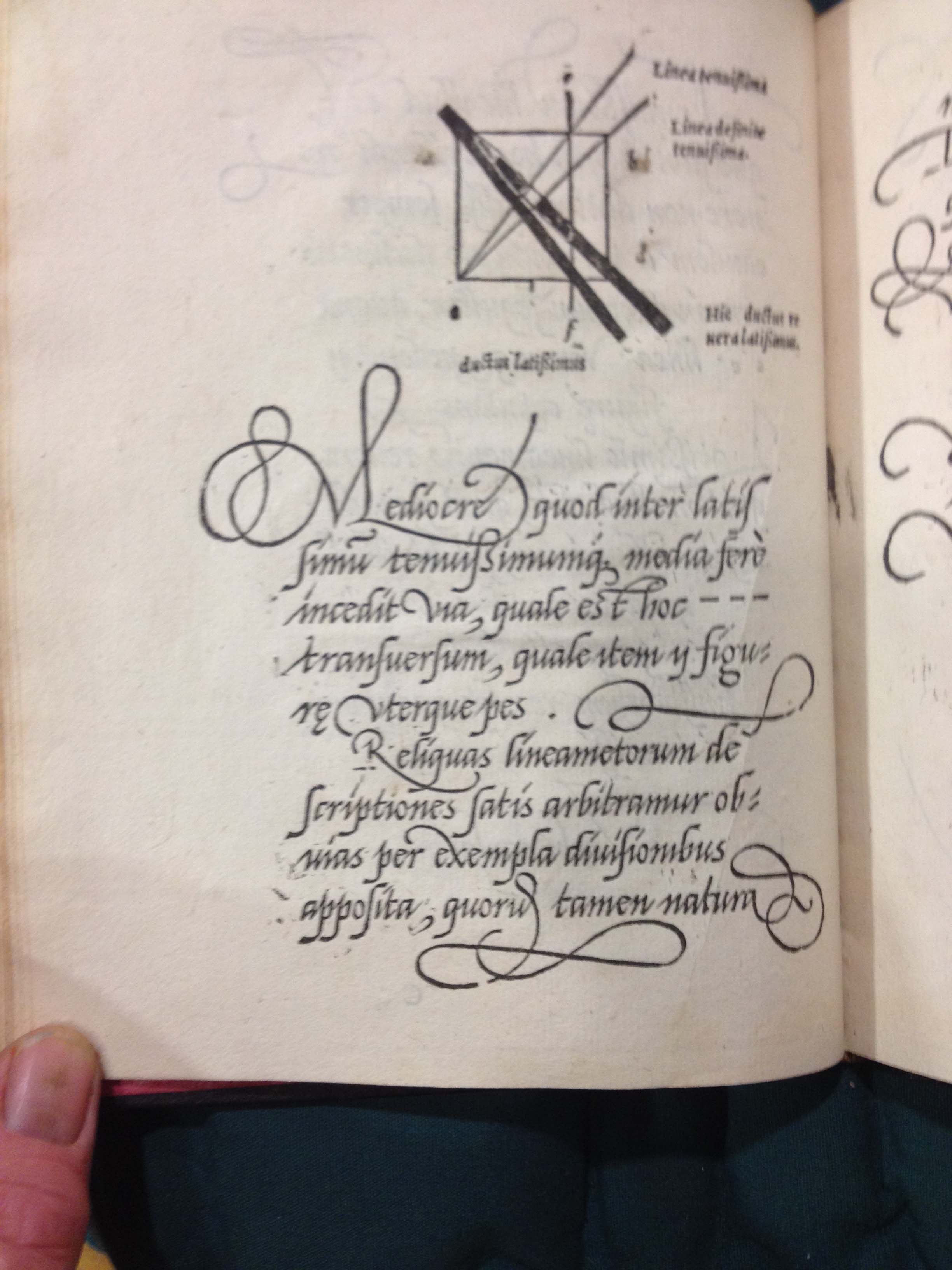

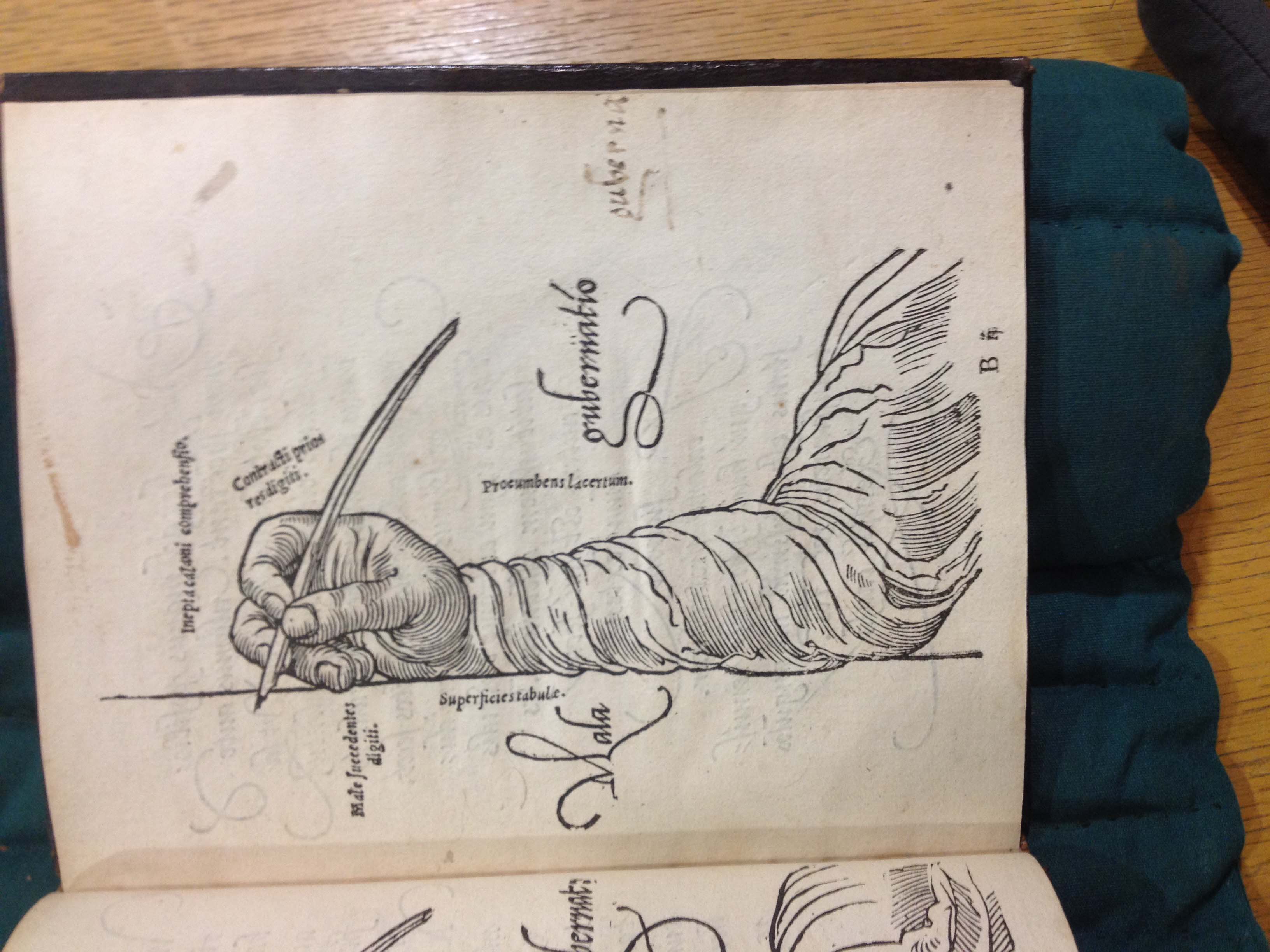

As you can see, Mercator went in for flourishes in a big way, even moreso than his Southern contemporaries.

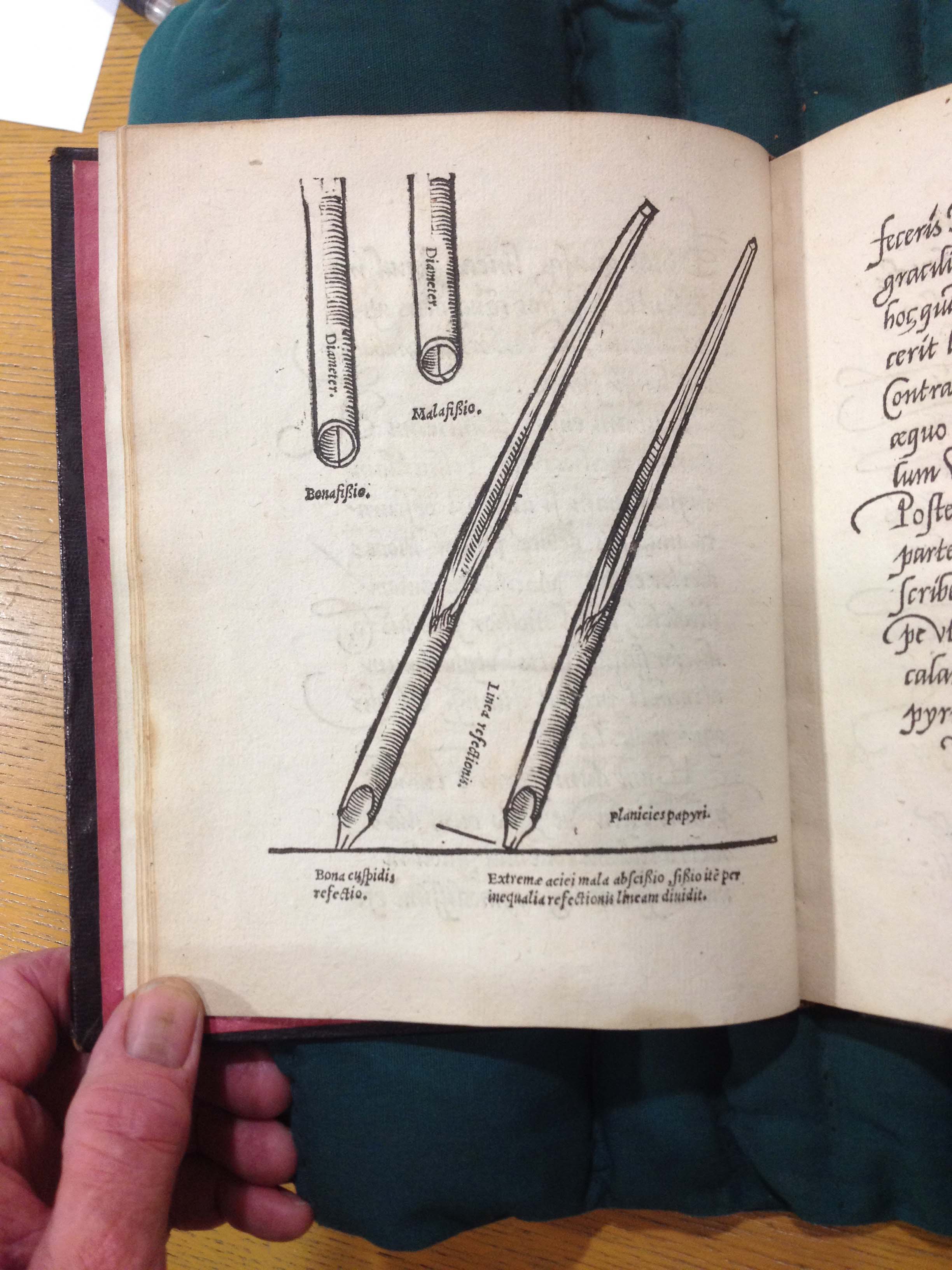

Gerhard Mercator had skill, energy and intelligence and was schooled in writing out texts in all the current hands. He particularly favored the Italic hand for maps and his skill as scribe and engraver led to work in making globes and soon after, maps. He could cut woodblocks as he does in this manual or engrave in copper as he often did for maps. This level of versatility in dexterity, aesthetic and mathematical skills produced an impressive oeuvre.

Whether describing how to hold the pen properly or cut a quill, Mercator's text is quite clear on how to do it.

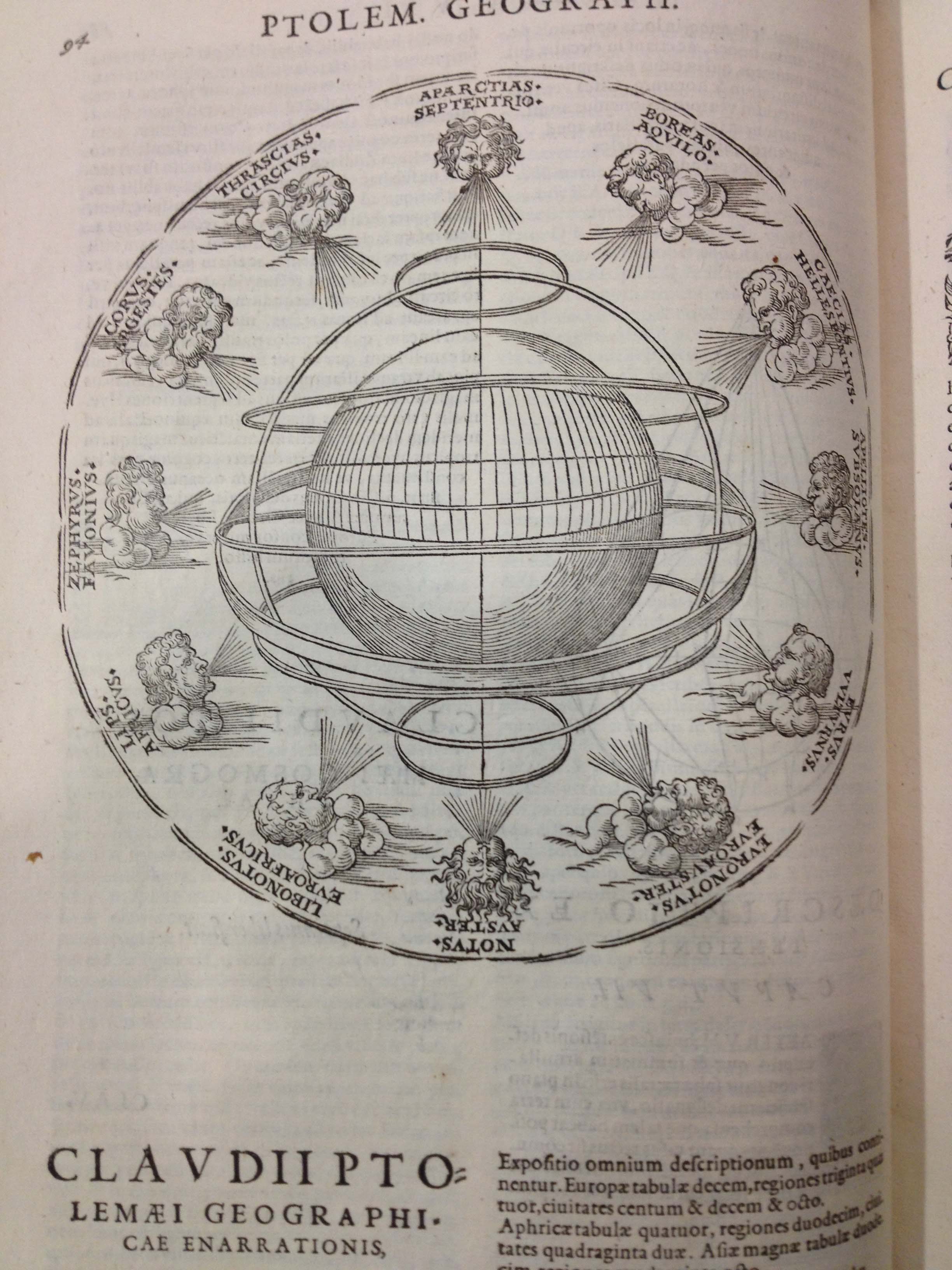

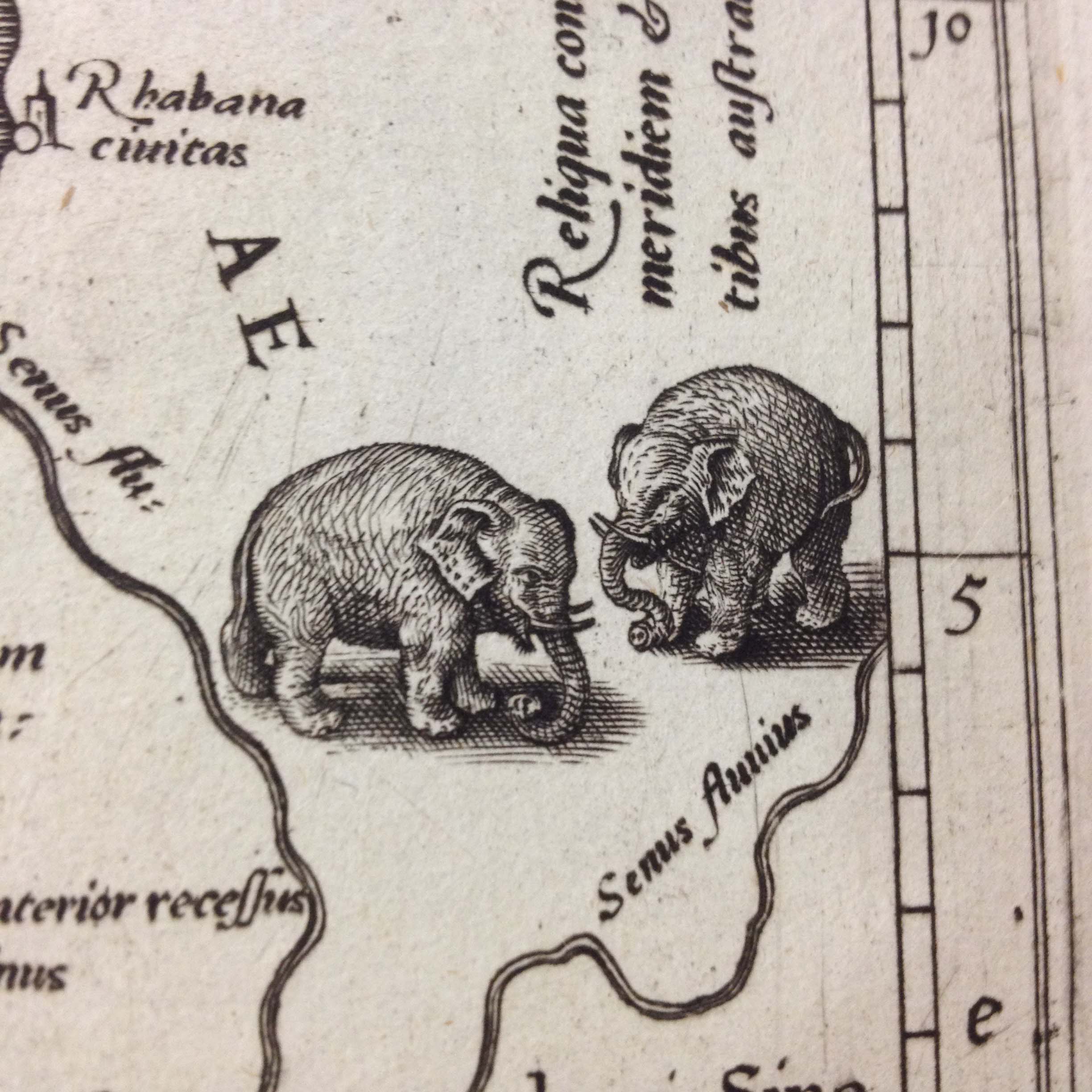

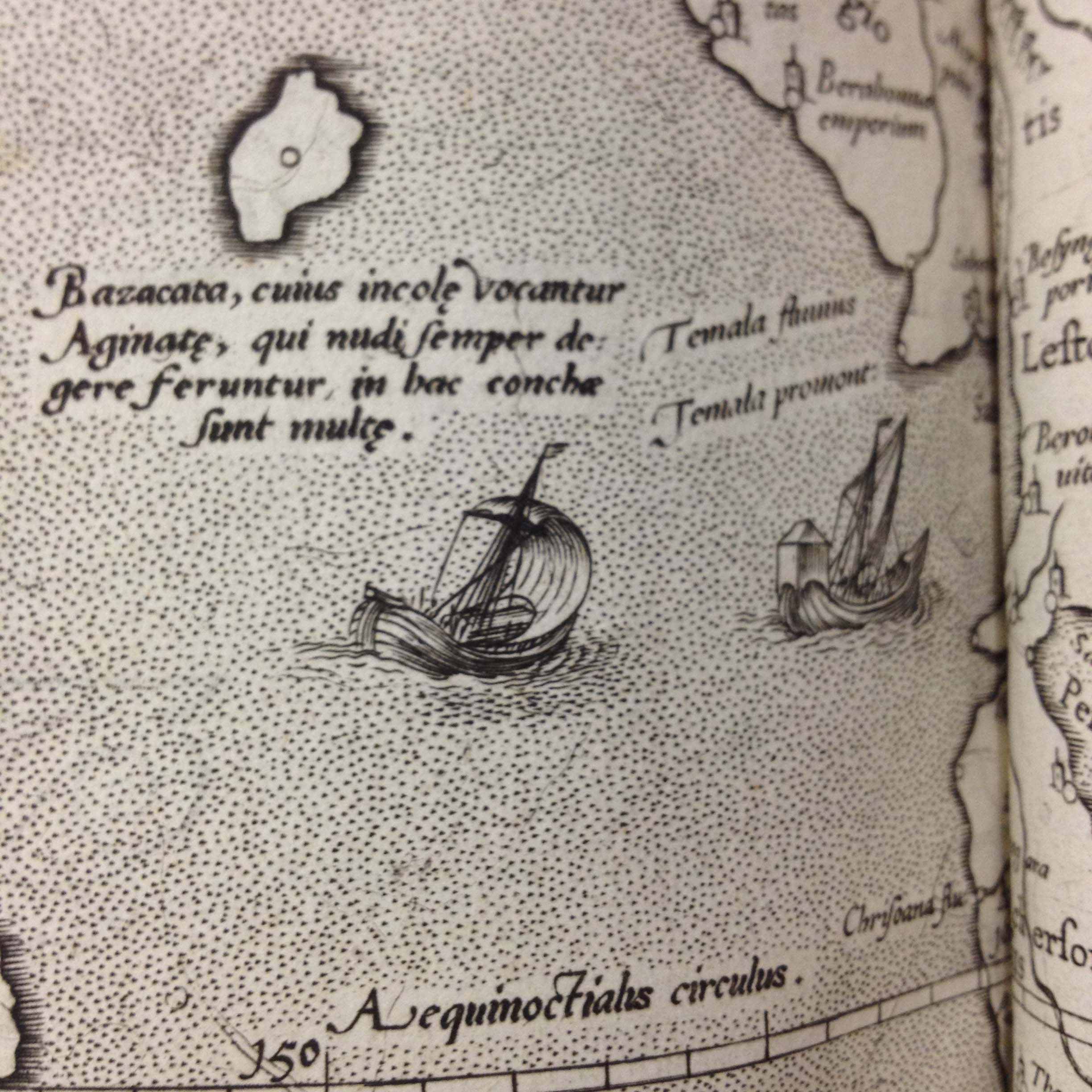

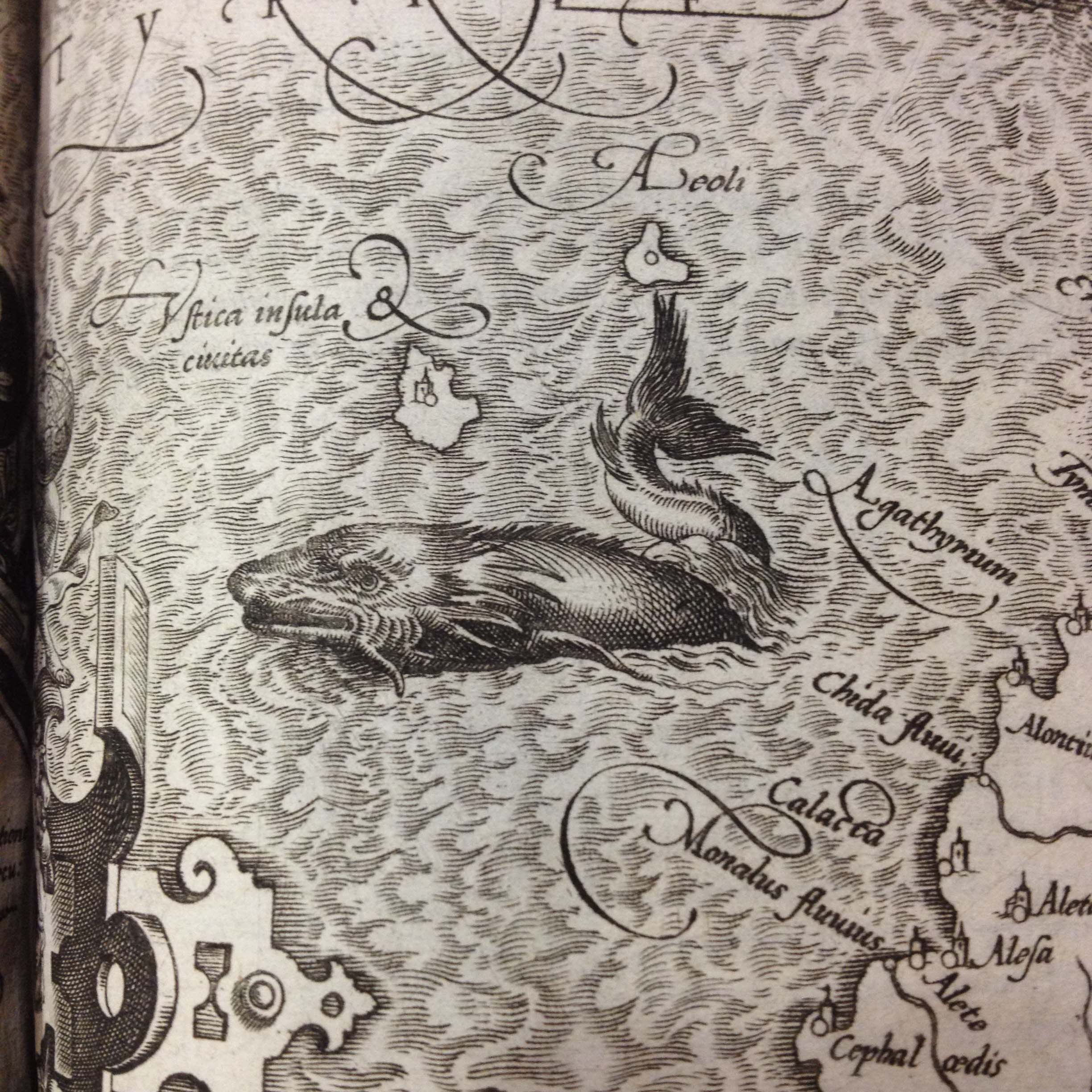

Since Mercator wrote on maps, not in books (though he surely did that as well) his graphic design and purpose for flourishing were for a different kind of reading. Maps were important tools for marine navigators to get around. The Mercator projection wasn't his invention, nor was it much used in his day. But let's not get hung up on gnarly navigation details and get to his engraved maps. That's where the fun in lettering and fantastical creatures of the sea are.

Mercator decided to show the Ptolemaic concept of the world in the 1580s and engraved maps based on this earlier world view.

Those flourishes may not be necessary, but they do look nice splashing around that sea creature.