Breaching the walls of the Folger Shakespeare Library

After a 2 month hiatus, I am back to recording progress on my trip. Coming back and re-establishing myself was more challenging than I imagined - in fact the trip itself was more challenging than I thought it would be. My apologies for leaving you hanging!

Getting into a special collection library can be daunting. University libraries have their system, public libraries have somewhat easier methods and private libraries can be the most restrictive. But things are changing in the library world and the vetting process has become a little less stringent.

The Folger Shakespeare Library requires letters from two individuals with .edu or .org email addresses. Generally that means an academic institution or non-profit research library. I was fortunate to acquire letters from one of each and the librarians said some nice things about me and my project.

I was excited that I was granted entry as a reader. I've visited the Folger's conservation lab a number of times, but going in as a researcher is different than visiting a colleague.

It was raining lightly on Saturday, September 11, 2015 when I rode to the library. My hosts live in Silver Spring, MD about 9 miles from the library, a 45 minute commute during the week. On a Saturday, it's faster as there is less traffic on the roads.

If I was going to be a riding reader, I should ride to the library at least once while in the nation's capital. I arrived somewhat damp in my riding gear. The guard didn't believe that I had permission to enter. After requesting my identification, she told me to stand in the lobby while she checked the reader services desk. I dripped water on the stone floor as I awaited my fate. Would I be allowed into this august library or be thrown out as motorcycle trash? The guard didn't appear to like a damp biker being allowed into the library. I guess not everybody in the library world has come to embrace motorcyclists?

Requests for items are made prior to arrival so the staff has time to page them, I'd made my request on Friday. Saturday, the hours are curtailed, so it makes sense to do this. Requesting vault or restricted items, they are pulled only during the week.

At the desk, I asked for my books and a young woman in jeans (librarians don't wear jeans, do they?) brought them to me. She asked why I had requested the particular books I had. Briefly (yeah, right!) I told her about Motoscribendi and my research. She listened attentively and then introduced herself as Heather Wolfe, the curator of manuscripts at the Folger. We stood there for half an hour talking about writing manuals, different calligraphic hands, quill cutting and the world of rare books and the chance to look at old books and manuscripts. It was like meeting an old friend and catching up. Heather's knowledge and enthusiasm are what makes this kind of work exciting. Meeting with an inquisitive, engaged paleographer happy to talk with me about these things gave me an even greater sense of being a part of something worth pursuing.

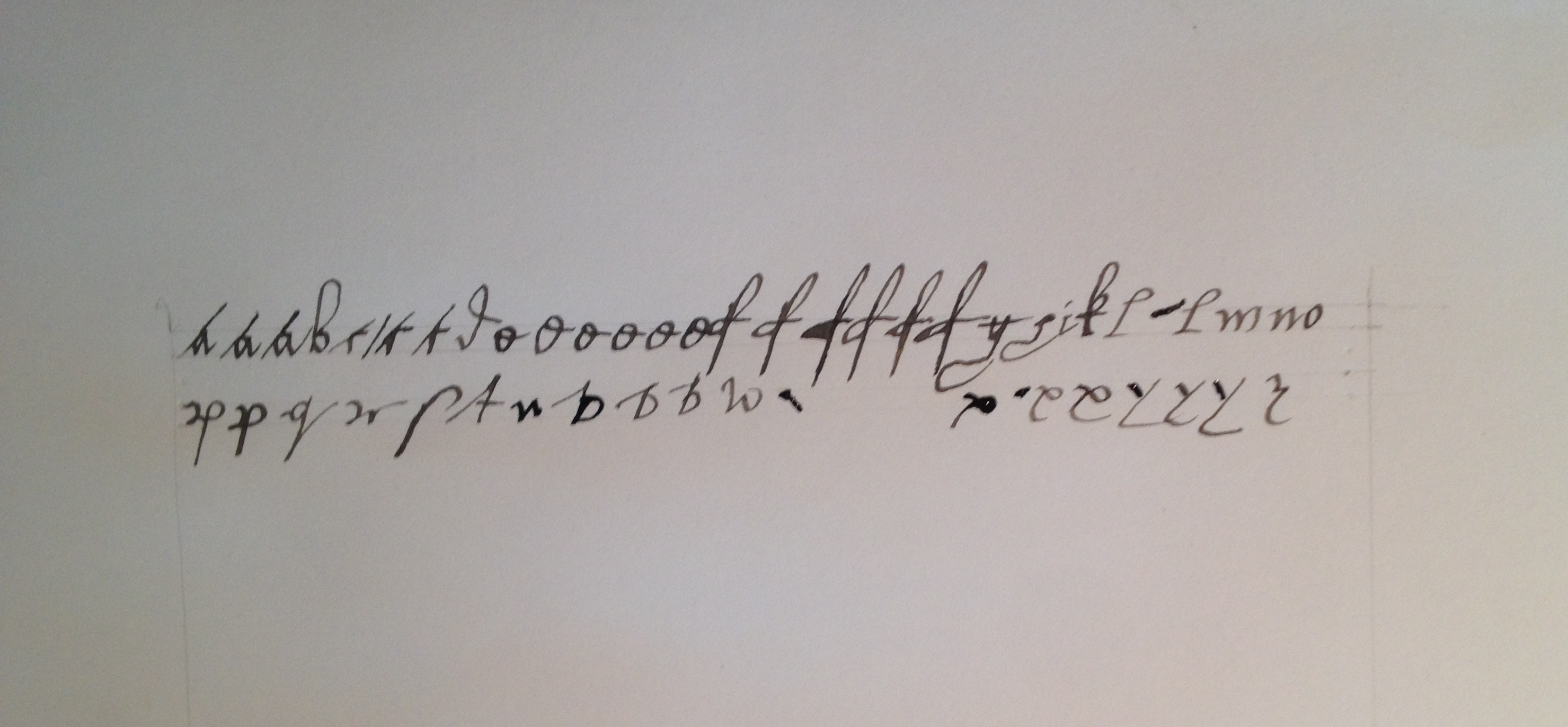

Heather teaches paleography classes on the Secretary hand at the library. Even though many manuscripts at the library are in English, they are all but indecipherable without some training. The library has around 60,000 manuscripts many of which are written in a Secretary hand. Heather and her colleagues have been working on a project to teach paleography and get people involved in transcribing documents from the collection. Early Modern Manuscripts Online (EMMO) has just launched Shakespeare's World to use crowdsourcing technology to allow interested individuals to be a part of reading and transcribing these manuscripts.

We talked about quill-cutting, parchment-making and other scribal traditions and how exciting it is to look at these materials and discover things about production and use.

When I went to sit down to look at the books, she apologized for taking me from my work, but the truth was that speaking with her is my work. Getting to look at books and learning more about these writing manuals is important, but I wanted to meet the scholars, librarians and staff that are charged with caring for these books.

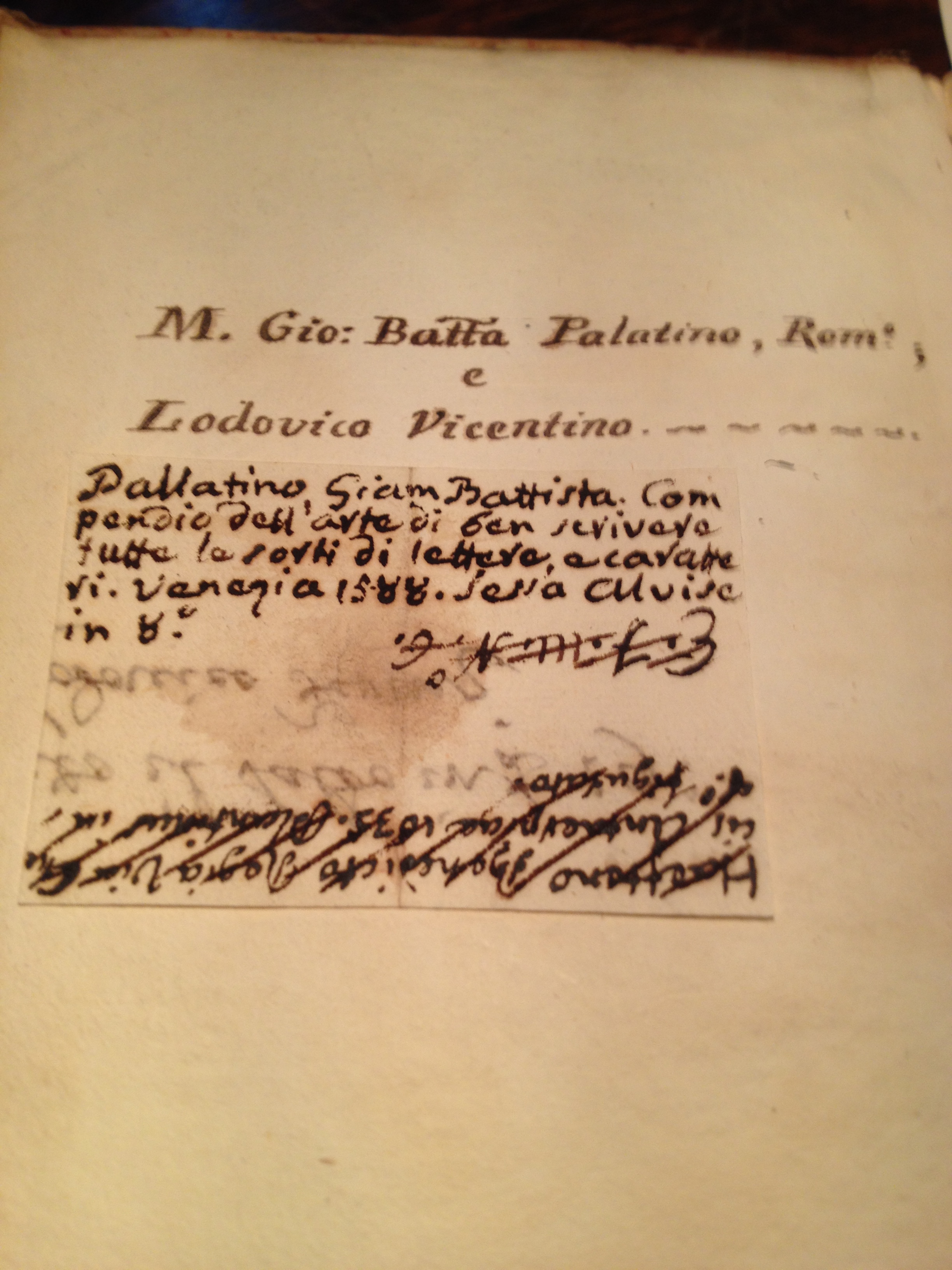

After lunch, I came back and continued looking at the books I'd called up. Palatino's writing manuals have been well researched by Stanley Morison and others, but I think there's more to learn by looking at these books. A digital copy will only represent one iteration. Each time I open a writing manual, I am excited to see how it has lived and been used.

This interplay of book and reader shows the challenge of learning to master a particular hand. Sometimes the student is not very skilled, and sometimes they are better. And often, the progression is obvious through the book's progression.

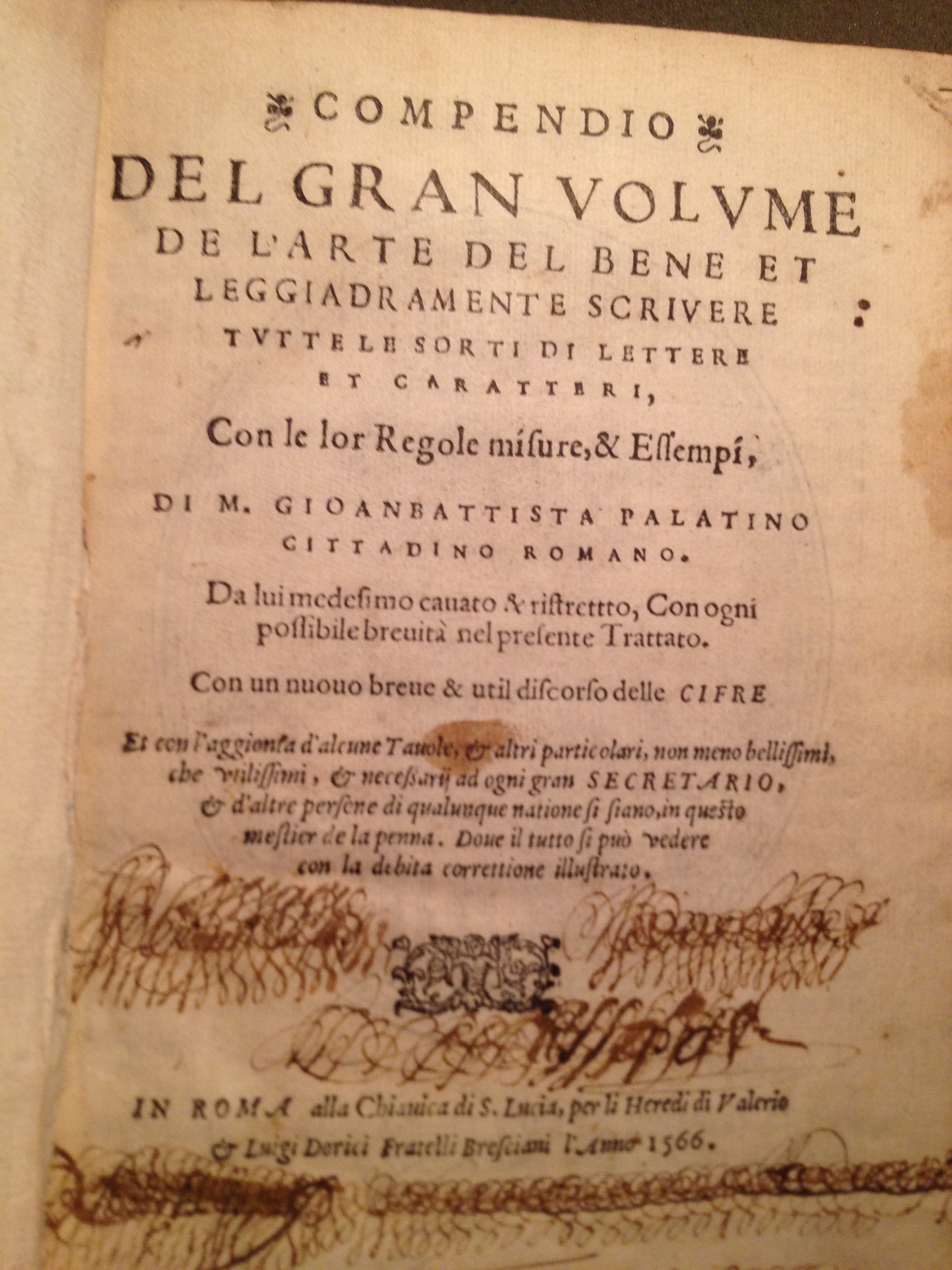

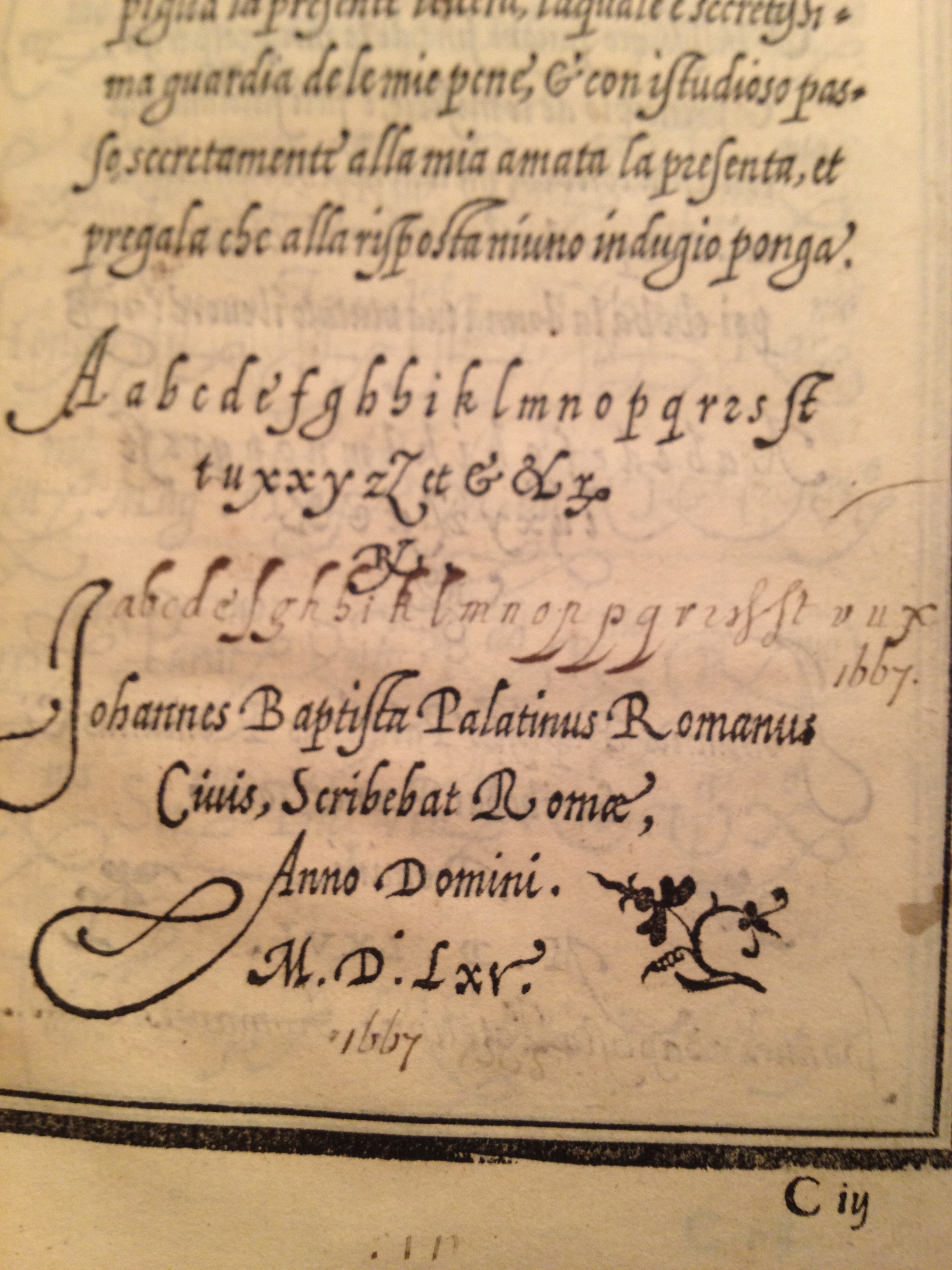

You see in the above image a woodblock that was cut in 1565 being used in the 1566 edition of the Compendio del Gran Volume. This block was cut a year before the printing of this book. It was the norm for woodblocks to be stored and reused in subsequent books. Typesetting for the later editions was newly done yet the woodblock is older. This copy then, has three distinct time element in this one page:

1565: Woodblock

1566: Typeset signature mark at lower right "Ciij"

1667: Manuscript practice, dated to a century later

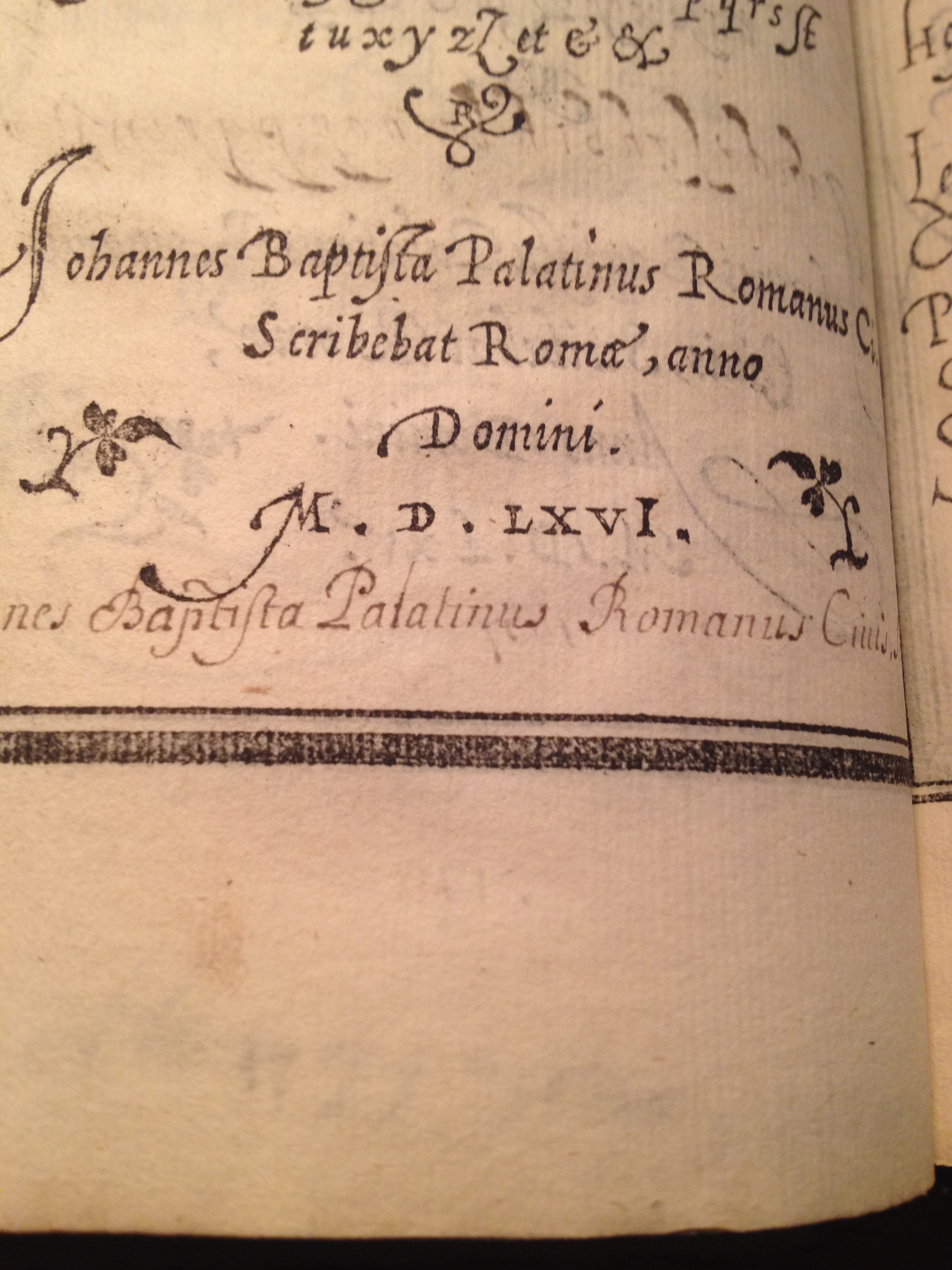

And on the verso of the leaf marked "Ciij" is another block cut a year later in 1566 with the same 17th century scribe's annotation of Palatino's full name.

There's more to discuss about the Folger's Palatino collection, and I'll continue that in my next post.