A Brief Stop at Winterthur

My time in Washington, D.C. had come to a close. After breakfast with my nephew Josh, I got on the road north. Well, almost North. I had a little fun with the toll roads in Maryland, getting onto one that required a toll reader that I didn't have. There's a ticket I didn't plan on.

Mid September along the Atlantic coast can be beautiful. I had experienced rain a week before while riding up from Richmond, but my ride this morning was fresh and crisp. Just a little cool - the summer's heat having lost it's intensity for the moment. I was still used to 95 - 100º weather, so the coolness of mid 70º air was welcome. Riding through Maryland along Chesapeake Bay and Delaware on I 95 is not necessarily a breath-taking ride, but it was pleasant on this particular day. My destination, Winterthur, DE is only 100 miles from my buddy, Mike's house, so this would be a short ride compared to my previous traveling legs.

Most people think of Winterthur as a decorative arts museum. That's because it is "the premier museum of American decorative arts." Writing manuals are not necessarily decorative arts, but they do fit naturally into Winterthur's collecting scheme because engravers, weavers, coach builders, and other craftspeople were called upon to include lettering in their decorative efforts. An engraver needs a sample alphabet on which to base the engraving. Monograms in bespoke items required a lettering guide for the artisan to follow and writing manuals often contained various lettering styles as guides.

After the invention of printing from moveable type, writing was still the primary means of recording unique or limited copies of master documents. However more opportunities for letters to be decorative arose with the freedom gained by mechanical reproduction of texts. This decorative trend can be seen in the earliest writing manuals. Writing masters were providing models for these craftspeople from the start. By the colonial period, copperplate engraved writing manuals illustrated a multitude of exemplars targeted to non-scribal purposes.

Winterthur's collection of writing manuals focuses on the 19th century American manuals, many of which were produced by the relatively new process of lithography. However, some were produced in the 18th Century and hail from Europe.

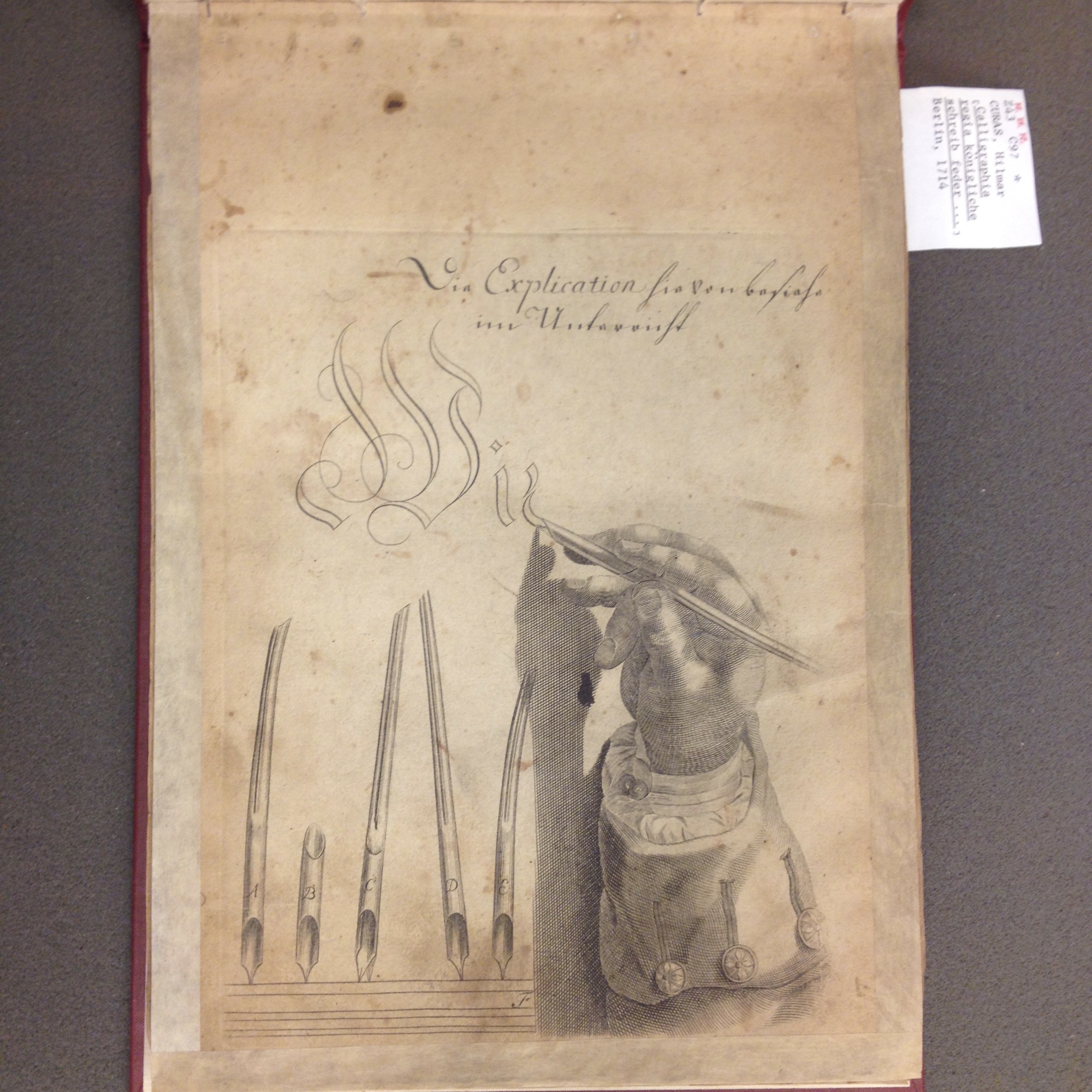

One such, Calligraphia regia konigliche Schreib Feder shows an illustration of quills cut at different angles for different hands. In one, there is a quill with two tips, showing how one quill nib is slipped over the other quill and rotated to create a double or outline letterform. I've seen illustration of a two-line letterform but didn't know how this was accomplished. This illustration is the first that I've seen to show a simple, effective method for making a split line letterform in one stroke.

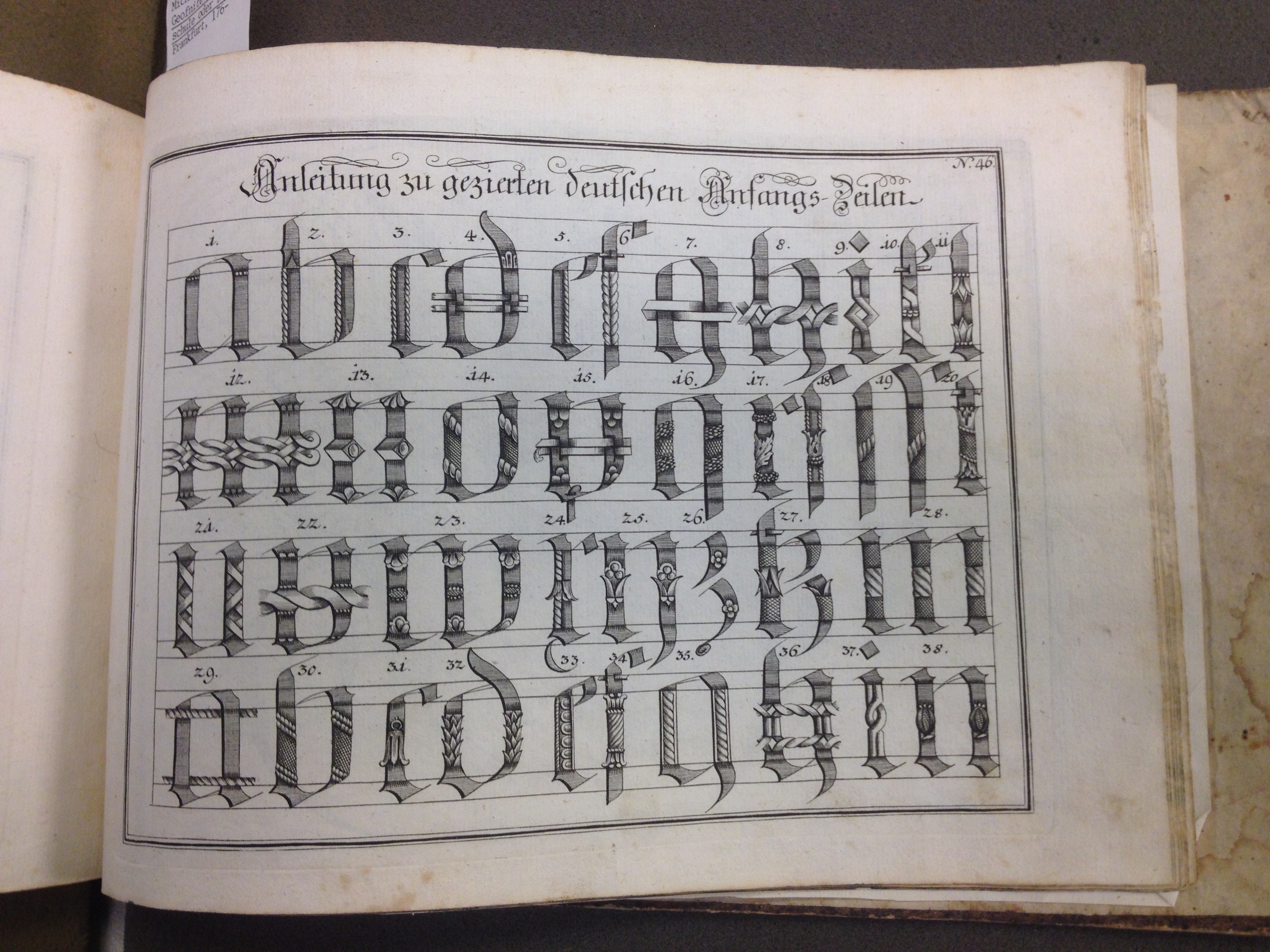

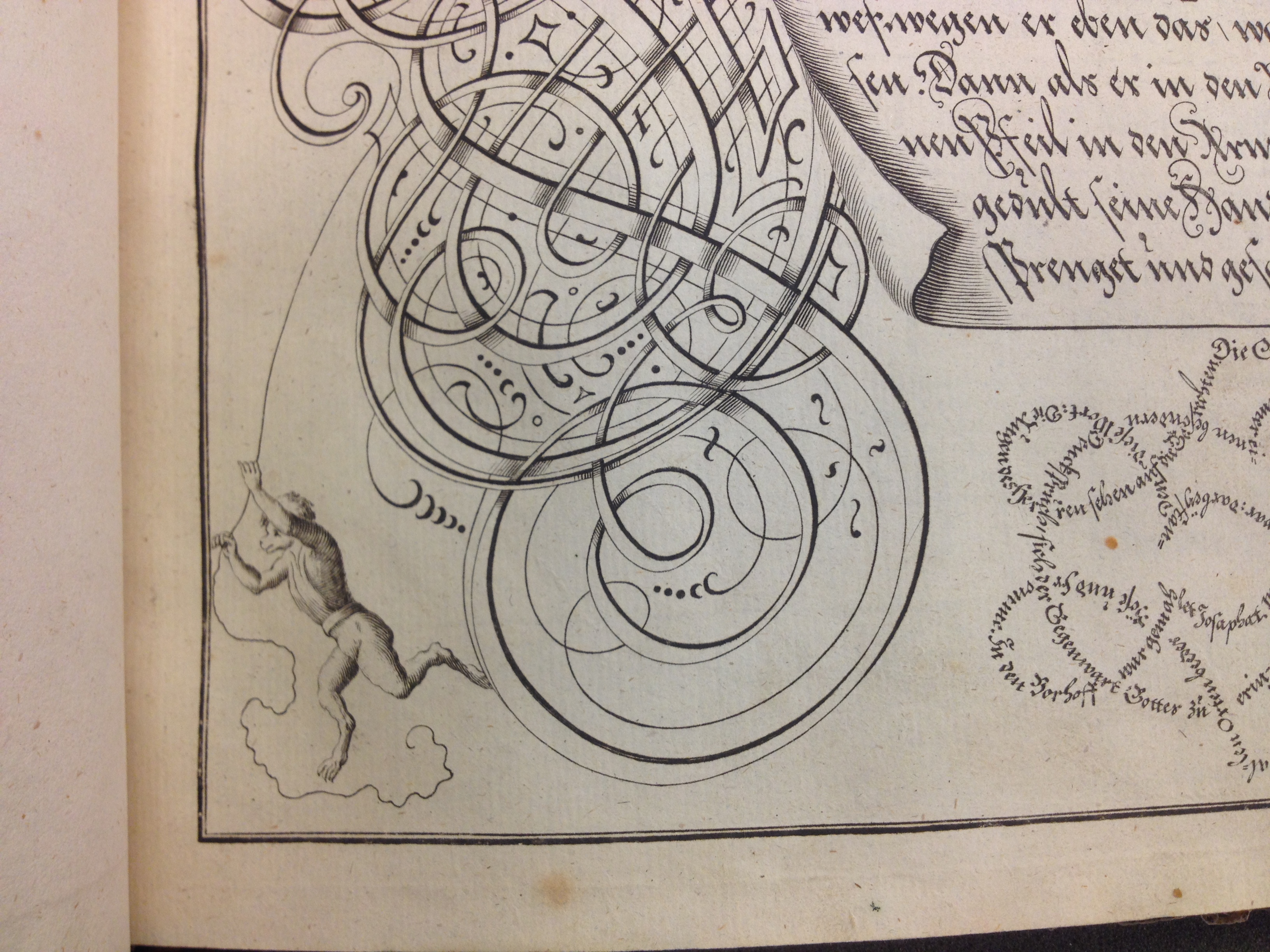

Decorative lace-like letters were all the rage in the 18th century, and they were quite ornate. Engravers may have used these as models for working silver or gold with an inscription.

[gallery ids="1663,1665,1666,1667" type="square" columns="4"]

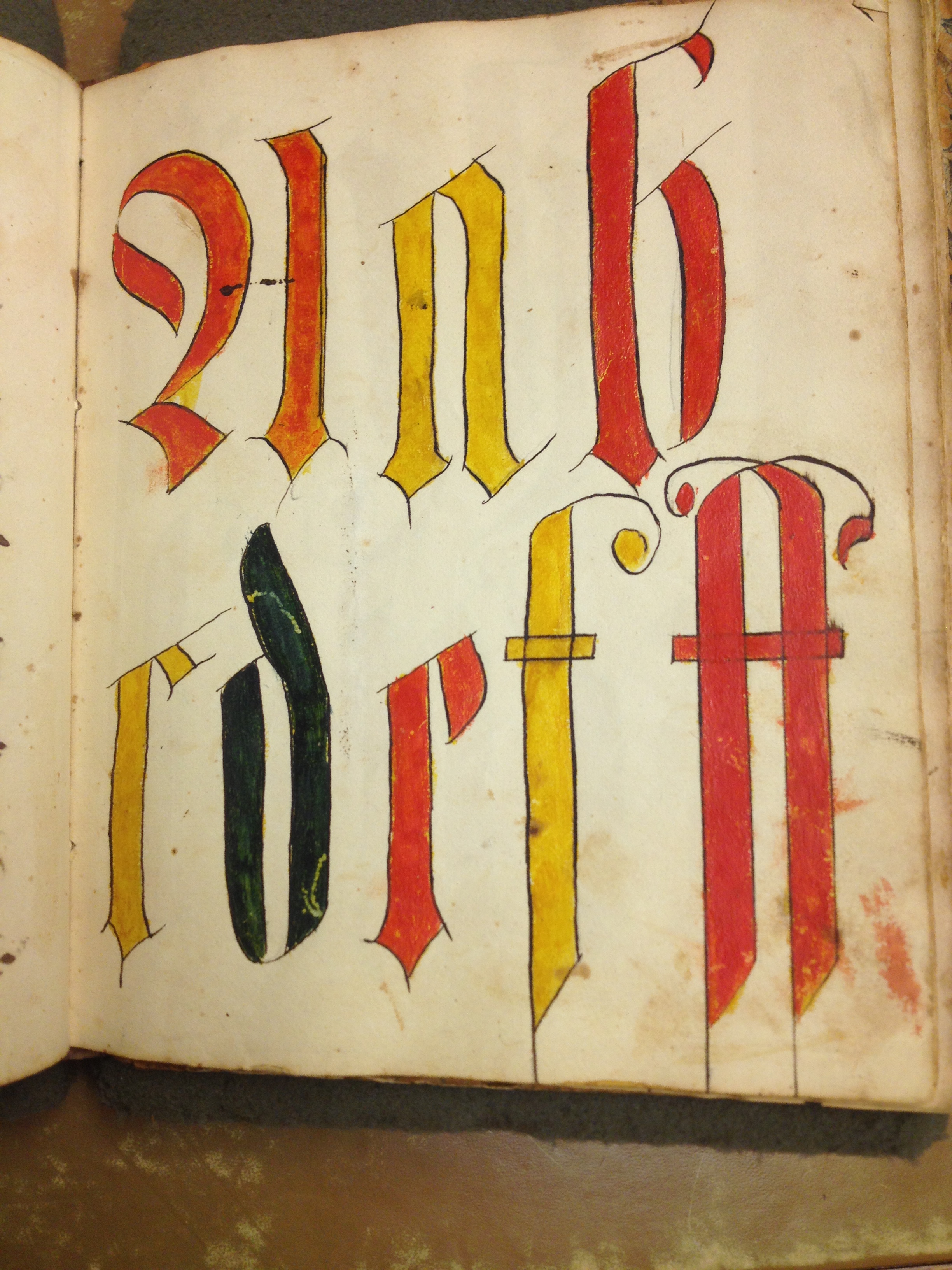

In this manuscript model book, there were many alphabets of various types, and single letters filling one page each.

And this colorfully whimsical page was a delight.

[gallery ids="1678,1679,1680,1681,1682,1683,1684" type="rectangular"]

The more ornate and decorative nature of these writing manuals shows a progression of the uses of writing manuals and clearly shows off letters as things worth looking at just for their beauty.

[gallery ids="1694,1695,1696,1698,1699" type="rectangular"] By the 19th century, there is a broadening of focus as to audience as demonstrated by this book. Now even Ladies should know how to write well as Miss Caroline Dashwood. She probably used a steel pen rather than a quill.

Having made it to Winterthur mid-day I only had about 3 hours to look at books and I decided that I'll have to come back for a longer is it.